Secondary Colors

There’s a photograph I’ve never taken. Midway up the butte I look north, across the green valley, to the sandstone hills beyond. The trees of the valley belie their surroundings, an oasis from an unseen well holding back the arid. The sandstone hills traverse a spectrum of deep red to orange then whites so bright the sun seems to burst from the rock itself. If I raise my eyes up slightly higher, I see the towering mountains add a third stratum to the untaken image. Gray spruce on the mountains recast the green of the valley in muted colors and eventually give way to bald granite and limestone. Finally, the sky, so bright I have to imagine it’s blue, completes the color field. I never brought my tripod to this spot; never marked the ground where I stood so I could return during that ephemeral moment, when the snowcap adds a penultimate veneer to the reflected light that passed through the lense to chemical and plastic. I wonder, however, if I had that photograph, would I feel the wind ruffle my shirt and the heat on my skin as I do now?

Mother’s Day The Handmaid’s Tale Style

Donald Trump’s “American Carnage” – Coming to a theater near you!

Accessing Mac Formatted Floppy Disks without a Kryoflux

One of the more common questions asked on the various digital curation forums is how to access HFS formatted 3.5” floppy disks. Variations on this question include: “why can’t my USB 3.5” floppy disk drive read old Mac disks?” or, “How do I access double sided double density (DS/DD) Mac disks?” or, “I have a stack of 3.5” floppy disks that neither Windows nor Linux will recognize, what gives?” However the question is formed, a common recommendation from the community is to use a Kryoflux controller card to capture the data from the drive. I’m a fan of the Kryoflux and recommend it regularly, but it does have several limitations, especially when it comes to cost, so I’ve been looking for alternative ways to access HFS formatted disks. While these disks are otherwise uncommon, because Macs were frequently associated with the works of “creatives,” they have an outsized importance in the world of digital archives, and thus merit some special attention. (Quick note: though 5.25″ floppy disks were used by the Apple II, “Macs” only ever used the 3.5″ diskettes, so if I say “Mac floppy disk,” I mean a 3.5″ diskette.) What follows are some recommendations based on my findings. In a way this is a followup to my article a few years ago on building a digital curation workstation and the blog post I wrote for MITH last year on using BitCurator to capture and access data on server hardware.

Some Background on Mac Floppy Disks

First let me explain the nature of the problem. One of the primary challenges of capturing data from floppy disks (either 5.25″ or 3.5″) is that the same form-factor was used across multiple generations of disk sizes and file systems. The Wikipedia entry on floppy disk formats is a great resource (bookmark it!), but even as exhaustive as it is, it’s still incomplete and doesn’t list all of the various computers and file systems that used the 3.5″ floppy disk. This presents a challenge because the same 3.5″ hard plastic diskette could have been used by a computer from 1985 or 1995, and in most cases with no indication about whether it’s from a Mac, IBM PC, Amiga, or other.

Apple alone used the 3.5″ floppy diskette for disks of three sizes: 400 KB (single sided, double density, or SS/DD), 800 KB (double sided, double density, or DS/DD), and 1.44 MB (double sided, high density, or DS/HD, or more commonly, just HD). What’s more, the 400 KB disks could have been formatted with either the short-lived Macintosh File System (MFS) or the more common Hierarchical File System (HFS). All 800 KB and 1.44 MB would be formatted with HFS. (The HFS+ file system originated with Mac OS 8.1, but because Apple moved away from floppy disks around that time, it is unlikely that you’ll see HFS+ formatted floppy disks.) I break all this down in the table below.

| Disk Type | Capacity | File System |

| SS/DD | 400 KB | MFS or HFS |

| DS/DD | 800 KB | HFS |

| DS/HD | 1.44 MB | HFS |

Variable-Speed vs Fixed-Speed Floppy Drives, or, Why Your USB Floppy Disk Drive Can’t Read a DS/DD Mac Floppy Disk

As I detail in my digital curation workstation post, a USB 3.5″ floppy disk drive will read both IBM formatted (Microsoft FAT12 file system) 720 KB and 1.44MB diskettes, but only 1.44 MB if they are Mac formatted (HFS). There’s a reason for this other than a general bias against Macs. Until the 1.44 MB floppy disks came out, Apple used a technology called a variable-speed spindle in their floppy drives, where as IBM-compatible systems used a fixed-speed drive. With this technology, Apple was able to eke out more space on SS/DD and DS/DD disks compared to their IBM counterparts, 400 KB to 360KB and 800 KB to 720 KB respectively. In the 1980s an extra 40k or 80k was nothing to be scoffed at, and Apple’s variable-speed drive was clearly the superior technology. But by the time the 1.44 MB floppies arrived, Apple was tired of being the odd-man-out, and adopted a fixed-speed spindle for its HD disks. Thus a present-day USB 3.5″ floppy disk drive is unable to read 400 KB (SS/DD) and 800 KB (DS/DD) Mac floppy disks because it uses a fixed-speed spindle and is unable to read floppy disks created with a variable-speed drive. This is also the reason that Windows software tools such as Omniflop are unable to read 400/800 KB Mac floppy disks.

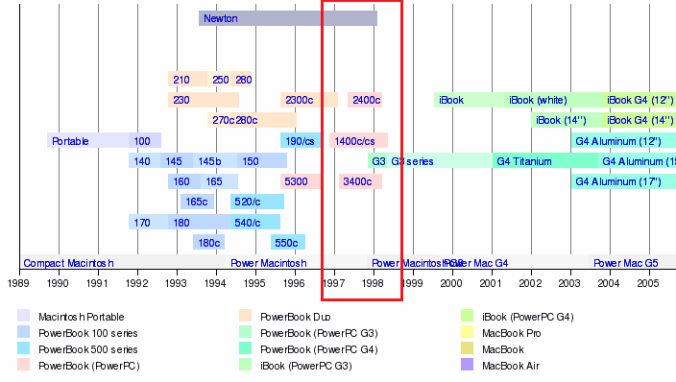

Moving to a fixed-speed floppy drive meant backward compatibility issues for Apple, as the image at the top of this post suggests. To address this issue, Apple began shipping its computers with what they called the “SuperDrive” (not to be confused with the 120 MB “SuperDisk” that came out in 1997), first with the Apple IIe and later with the Macintosh II. The SuperDrive had the capacity to read both variable and fixed-speed formatted disks, as well as IBM formatted disks on a Mac. (Just to make things nice and confusing, once 3.5″ floppy drives were retired, Apple repurposed the “SuperDrive” name for its CD-ROM drives, urg.)

There’s one more wrinkle to this history that might get in the way of the digital archivist. As the 1.44 MB floppy disk became the industry standard, there was little or no reason to support 400KB disks going forward, so in 1997, with the release of OS 8, Apple dropped support for MFS. The upshot being that if you happen to have 400KB Mac floppy disks formatted with MFS, then you need a system running Mac OS 7.6.1 or older to read them. And while MFS formatted disks may be rare, any and all Mac disks from 1984 to 1986 would be MFS formatted because it was the only option availabe.

Mac 400/800KB Access Methods

As stated above, the most common recommendation for accessing data on legacy Mac floppy disks is using the Kryoflux, which works. However, I see two main problems with using the Kryoflux. The first is cost. For institutional use the costs for a Kryoflux and software license are (at last check) around $2,500. Not insurmountable, but not chicken feed either, and beyond the means of many smaller collecting institutions. The second issue I have with the Kryoflux is that it requires three steps to actually view the contents of a disk. First you capture a stream of the magnetic fluxes, second you encode the stream into the appropriate format for the disk type and create a disk image, and then finally you mount the disk image on either a working Mac or through an emulator. This multi-step process is fine if you know that you want the contents of the disk, but if you’re still just appraising the disks and aren’t sure the content is of value, that’s a lot of extra work.

An alternative to the Kryoflux approach is to purchase or find an older Mac system with a 3.5″ floppy SuperDrive, which at the time of this post can be had for $100 – $200 on eBay or Craigslist. This is not a new idea, obviously, but the trick is knowing which legacy Mac systems would make the most useful inclusion in the digital archivist’s toolbox. These access systems, what Doug Reside calls “Rosetta Computers” (see page 20 in the PDF linked here), need the capacity to both read legacy floppy disks and transfer that data to a newer system vie network or other means. In the link above, Doug recommends the Macintosh PowerBook G3 “Wallstreet” edition because that particular laptop was the last Mac to ship with the 3.5″ floppy SuperDrive. After that, Mac systems shipped with regular 3.5″ floppy drives, including the two PowerBook G3 editions that followed the “Wallstreet” edition (named “Lombard” and “Prismo”, and noted for their bronze looking keyboard). This is a solid choice, and one used by MITH on a number of digital preservation projects. However, the PowerBook G3, regardless of edition, shipped with Mac OS 8.1, which meant that it cannot read MFS formatted 400KB disks. For that you will need a Mac running System 7.6.1 or older.

Recommended Macintosh Access Systems

So which Macintosh systems should the digital archivist add to their toolbox in order to access/appraise a complete range of legacy Mac floppy disks? There are a number of possibilities, but primarily the access system should meet the following three criteria:

- The system includes a SuperDrive 3.5″ floppy drive

- The system can run Mac OS 7.6.1 or older

- The system includes the means to easily transfer data to a modern computer (ideally via network)

Number three above is a somewhat optional because in a sense every system with a SuperDrive includes its own transfer method: simply create a disk image of the SD or DD disk and then copy it to a 1.44MB HD disk which can then be read by a USB floppy disk drive. This “sneakernet” method, however, gets us back to a troublesome multi-step process, so I recommend looking for a legacy system that either includes an Ethernet jack or, for desktops, has the capacity to add on a USB expansion card.

Below, then, I offer some recommendations. I am indebted to Sonic Purity and his article “Working with Macintosh Floppy Disks in the New Millennium” for many of these recommendations, and also much of the technical details above. For those interested in a more in-depth description of Mac floppy disks and their history, I highly recommend it.

Laptop Recommendations

This series of PowerBooks are the immediate predecessors of the G3 models discussed above. While I would usually recommend the PowerBook G3 “Wallstreet” edition, all PowerBook G3 laptops shipped with Mac OS 8.1, and thus won’t read MFS formatted disks. The PowerBook 1400c and 3400c offer performance close to that of the G3, but with MFS support. If you can find one of these laptops in working order, this is perhaps your best option because they are a self-contained computer–no need to buy keyboard, monitor and mouse separately. A few things to keep in mind if you go with a PowerBook:

- The 1400c and 3400c have swappable drive bays that can hold a floppy drive, Zip drive or a CD-ROM drive. Make sure the system you buy includes the floppy drive at the very least, but opt for the Zip drive as well if you can find one because…

- Only the 3400c has Ethernet capacity built in. You can add Ethernet support to the 1400c through a PC card (aka, PCMCIA card), but the chances of finding one that has drivers for the 1400c are slim. For this reason, I strongly recommend the 3400c if you can find one.

Desktop Recommendations

Power Macintosh 7200 – 7600 / 8200 – 8600 / 9200 – 9600

These computers were built and sold from 1995 to 1998 and were the first generation “Power Macintosh” systems before Apple added the G3 (and subsequently G4 and G5) naming convention. Each of these Power Macintosh systems can run Mac OS 7.6.1, include a SuperDrive floppy disk drive, and come standard with a 10base-T Ethernet network jack–everything you need to access the full range of legacy Mac floppy disks and transfer the images to a modern computer. (The 7100 and 8100 models are not recommended because they don’t include an Ethernet jack.)

Thus, the full list of potential “Rosetta” systems for reading Mac floppies would be:

- Power Macintosh 7200

- Power Macintosh 7300

- Power Macintosh 7500

- Power Macintosh 7600

- Power Macintosh 8200

- Power Macintosh 8500

- Power Macintosh 8515

- Power Macintosh 8600

- Power Macintosh 9500

- Power Macintosh 9515

- Power Macintosh 9600

Acquiring you Legacy Mac Access System

The easiest option for acquiring one of these systems is, of course, eBay. At the time of this writing there were about a dozen of the above systems (desktops and laptops) for sale on eBay, with prices ranging from $50 to $250. Craigslist and computer recyclers are also options. However you acquire the system, be prepared to do a little work on it–installing Mac OS 7 at the very least. Common issues you might expect are a missing power cord or a missing hard drive. Keep in mind that there is a finite number of these legacy systems out there, and at some point in the not-too-distant-future, they’ll be gone. Acting now to build this access capacity in your digital curation toolbox will make you look very smart the next time someone hands you a box of legacy media and asks you to figure out just what the heck they’ve acquired.

The Kryofux is a powerful tool, and given the means, the digital archivist should have one at her disposal. However, even discounting the expense, they are still an imperfect access tool because they require so many steps to view the disk’s contents. For $100 to $250 and a little TLC, a library, museum or archive can expand its capacity to read the full-range of Mac floppy disks and conduct appraisal and analysis of the content quickly and easily.

It seems like….

Write Blocking and le Mal d’Légal

An archives is in many chases defined by what it excludes more than what it includes. Sometimes referred to as archival silences, these exclusions articulate and express the power dynamics extant in the culture (understood broadly) of which the archive is an expression. On the one hand we might think of the silences and exclusions as overt political acts, as they surely were during the period of European colonial expansion, and more recently exemplified in the damning colonial archival records the UK government successfully kept out of the public eye for decades. However, such exclusions may also be technical in nature; that is, the structures, policies, and systemic workings of institutions and archivists may pose barriers to certain types of information. In a digital context this systemic, rather than political, act of technical exclusion is observable in the object of the forensic write blocker—a device that intercedes between digital carrier media such as flash drives and hard drives and the digital storage of the archive. As the name implies, the write blocker “blocks” data from being written back to the original media in an effort to guarantee the authenticity of the bitstream, the pattern of ones and zeros read from the media. This inbetweenness invites us to think about the write blocker at the level of topos and its uniquely situated space between the archive proper and the original object. Considered in terms of Jacques Derrida’s Archive Fever, the write-blocker performs the tension Derrida examines between topology and nomology, location and law.

Write blockers are used by digital archivists as they read electronic data stored on volatile media and move that data to a more sustainable environment, usually a digital repository of some type. Because computers function by default in a read/write mode, simply connecting a hard drive or flash drive to a computer can cause data to be written to the drive, potentially overwriting deleted or temporary files. An archivist concerned with maintaining an authentic copy of the original media will work to ensure that such writings back do no occur during the capture process. To facilitate this authentic transfer, digital archivists have borrowed from the digital forensics community and employed hardware and software write protection. My comments here will focus on hardware write blockers, the physical devices that intercede between the original media and the archivist’s workstation.

Forensic write blockers emerged out of a need by law enforcement to ensure that in their investigation they do not contaminate the data contained on digital media gathered from a crime scene. Their need is twofold: First, the examiner knows that any incriminating data recovered from a hard drive or other carrier media will likely be found in the digital traces of deleted files or swap space (the “virtual memory” a computer uses when it runs out of RAM). An incautious approach could inadvertently overwrite this content because its location on the physical media it is considered blank by the file system, and therefore available for new data. Not attaching a write blocker before capturing data from a suspect’s carrier media would be tantamount to sweeping the floor of a crime scene before beginning the examination. Second, in the event that the examiner finds incriminating evidence on the carrier media, they must be able to demonstrate to the satisfaction of a jury that their process was sufficiently cautious and did not affect the original data. I recount this here in order to link the write blocker used in a digital archives to its nomological origin. A write blocker carries with it the signifiers of law enforcement, performing in an archival setting Derrida’s contention that archives function as “the intersection of the topological and the nomological,” which he subsequently shorthands “topo-nomology” (3).

There are three ways to consider the topology of a forensic write blocker in the context of a digital archive. First, is the write blocker’s physical inclusion in the substrate that compose the digital archive. Second, the space it occupies in the input/output (IO) system. And third as an abstracted object that is represented in an archival workflow. I have alluded to the significance of the physical object adopted into the digital archives from the digital forensics world above, so let me address the second two topologies in further detail. Write blockers vary in type, but essentially they function by providing connectivity between IO systems. For example, typical hard drives have one of two IO systems: an IDE data bus, or a SATA data bus. A hard drive write blocker includes the proper power and data bus cabling that allows a drive to connect to the write blocker as an input device. Data that passes through the write blocker is then output through a USB cable to the computer where the disk capture is being performed. In addition to its named function, a write blocker also serves as a translator of sorts, meshing two disparate IO systems and allowing data to flow between them. Thus the write blocker inhabits an intersticial topos, a space that simultaneously facilitates data transfer while, ironically, also preventing it.

In this intersticial space the write blocker performs an archival silencing by eliding its own presence in the archival record. In this sense write blockers (and write blocking) exemplify Derrida’s concern with the death drive within an archives. After recounting Freud’s practice of questioning if anything he wrote actually needed to be written down, or published, or archived, Derrida considers Freud’s self-effacing impulse by comparing it to the psychoanalytic concept of the death drive. He writes, “[The death drive] is at work, but since it always operates in silence, it never leaves any archives of its own. It destroys in advance its own archive, as if that were in truth the very motivation of its most proper movement. It works to destroy the archive: on the condition of effacing but also with a view to effacing its own ‘proper’ traces” (10). Such is the role of the write blocker in a digital archive because any write blocker that would leave an archives of its own activity would cease to function as a write blocker. This small, seemingly insignificant device becomes the example par excellence of what Derrida means by “archive fever.” For, as he writes later, “The death drive is not a principle. It ever threatens every principality, every archontic primacy, every archival desire. It is what we will call, later on, le mal d’archive, archive fever” (12). That part of the archive that prevents the archivization of itself–the archival death drive–finds its digital surrogate in the forensic write blocker, an ouroboros figure eternally consuming itself.

It is not inconsequential here that Derrida sees the death drive effacing what he calls a “proper trace,” which begs the question: what then counts as an improper trace? What an improper trace my look like I will set aside for now, but this emphasis on traces returns us to the nomological role of the write blocker. As mentioned above, a write blocker that leaves a trace of its own intervention would cease to be a write blocker. This self-negation has a second theoretical resonance when considered in the context of forensic science. Specifically and ironically, write blockers actively work to disprove or side-step the forensic axiom that “every contact leads a trace” (known as “Locard’s exchange principle,” named for forensic science grandee Edmond Locard ). And yet here is a tool developed for and by the digital forensics profession that actively contradicts one of its founding principles. Thus, in either an archival or criminal investigatory setting, the write blocker’s first priority is to elide itself, to disprove the maxim which ultimately lead to its creation. By standing as an obvious yet necessary contradiction to the Locard principal, the write blocker demonstrates the role of the death drive not just in archival science, but in forensic science as well, a le mal d’légal if you will.[1]

A third topos occupied by the forensic write blocker in a digital archives is its position on the workflows and processing documents of collecting institutions. Despite the abstracted nature of this topos, it is here that the forensic write blocker has its most pronounced effect on the archive. In its physical form and as a tool of the digital archivist, the write blocker demonstrates the topo-nomological nature of the archive by merging the legal substrate from which a write blocker emerges and the situatedness of the write blocker in archival practice. However, when we abstract out the idea of the write blocker and consider it in terms of a step in a workflow, we see how Derrida’s sense of technology’s influence on the archive is played out.

For Derrida, technology is more than a convenience or tool for increased efficiency. Rather, technology has the capacity to completely reshape our understanding of the archive. We see this in his analysis of e-mail and the potential email has to radically reshape psychoanalysis. Derrida writes, “[P]sychoanalysis would not have been what it was (any more than so many other things) if E-mail, for example, had existed. And in the future it will no longer be what Freud and so many psychoanalysts have anticipated, from the moment E-mail, for example, became possible” (17). Derrida argues that because so much of psychoanalysis research came in the form of hand written letters between practitioners, had technologies such as e-mail existed during the early development of the field, they would have rendered what we now consider psychoanalysis unrecognizable. Likewise, from the moment e-mail emerged as a dominant form of communication, psychoanalysis’s future diverted from whatever intellectual trajectory it may have been on to one now influenced and facilitated by the new communication technology, much like the ever evolving alternate timelines spinning out of the Star Trek universe.

Of course, the advent of e-mail has been disruptive well beyond the confines of psychoanalytical thought—it has had profound effects on all aspects of human communication, particularly in the archive. Derrida notes this significance by writing, “[E]lectronic mail today […] is on the way to transforming the entire public and private space of humanity. […] It is not only a technique, in the ordinary and limited sense of the term: an unprecedented rhythm, in quasi-instantaneous fashion, this instrumental possibly of production, of printing, of conversation, and of destruction of the archive must inevitably be accompanied by juridical and this political transformations” (17). E-mail is more than a convenience, it reshapes how we represent and record the world, and as such it must have profound legal (nomological) implications as well. Though this is something of a dated example twenty years on, replace “e-mail” with “twitter” or any other disruptive communication technology and the argument still holds. E-mail here serves only as an example of how interventions of what Derrida calls “archival technologies” can radically reshape not just the archive, but archivization itself.

The profoundness of these changes are not simply that they necessitate a change in process, but that they necessitate a change in the fundamental logics that frame a discipline. In an almost heretical tone, Derrida writes, “[I]f the upheavals in progress affected the very structures of the psychic apparatus, […] it would be a question no longer of simple continuous progress in presentation, in the representative value of the model, but rather an entirely different logic” (15). Technological upheavals, then, have the capacity to force psychoanalysis to do more than seek better models, better representations; they have the capacity to necessitate the abnegation of the model itself. Out with the id, ego, and super ego, and in with the… what? What logic will pertain after a theory of the psyche is filtered through a new technological apparatus?

While not as significant or transformative a technology as e-mail, the forensic write blocker carries with it its own potential to reshape archival theory and practice. A common point in a digital preservation workflow reads, “connect to write blocker,” usually before a carrier media is connected to a workstation for data capture. In the context of Derrida’s analysis of e-mail, it is not unreasonable to ask the questions: 1) what was the standard practice before forensic write blockers became a common tool in a digital archive? And, 2) if there had never been a point where digital forensics tools and practices had been adopted by digital archivists, how would that affect both past and future collections? To address the first question, there are undoubtedly digital collections captured without the application of a write blocker. Those collections stand in contrast to post-write blocker processed collections in that the act of collection itself is now visible, now leaves a trace on the original media and on the captured bitstream. Data of either trivial or significant quality has been overwritten in the capture process, fundamentally altering the object of capture, especially in the occluded spaces behind the file system’s veil. This alteration may be a product of ignorance, of a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature the digital object, but it is also a repudiation of the self-effacing death drive that Derrida identifies as “archive fever.” The archive archives itself when the write blocker is absent and the digital capture includes a record of itself.

Of the second question, what would be the effect if a digital forensics sensibility hadn’t made its way into archival theory and practice? Absent a digital forensics—a nomological—understanding of digital objects, there would be no need for a forensic write blocker. If there is no need for a write blocker, then digital archival theory and practice would by default adopt a sense that only data represented by the file system is significant. The traces and inscriptions we know to be fundamental to digital representations would be overlooked in favor of their abstracted representation, and, to borrow from Derrida above, such a destruction of the physical inscriptions “must inevitably be accompanied by juridical and political transformations.” If the power of the archive is to define what can and cannot be archived, then the adoption of a file system-centric approach to digital archives abdicates staggering power to corporate and governmental institutions that design and propagate those file systems. The potential for such an abdication is not mere speculation; the current debate in the United States over whether or not Apple Computers must provide a “back door” into their encrypted iOS file system for the purpose of law enforcement demonstrates just how much power is bound up in the representation and structuring of digital data. Thus, the presence of “connect to write blocker” in a digital preservation workflow carries with it the weight of a digital forensics ethic and understanding that values the physical inscription, however inaccessible and problematic, as the primary archival record rather than its abstracted representation. Understood together, the answers to these two questions demonstrate just how, like e-mail, the past and future of the archive are radically reshaped by the advent and inclusion of the forensic write blocker in archival workflows.

Because of its unique positioning as both a physical object and as a theoretical principle, the forensic write blocker helps us contextualize Derrida’s theory of the archive in a digital sphere. At the level of practice, the write blocker’s inclusion in the space of the archive builds into the substrate of the archive the forensics law enforcement from which it emerges, in a sense performing Derrida’s hyphenation of topo and nomology. More significantly, however, the presence of the write blocker—or the concept of write blocking—signifies an archival practice that has discarded a file system-centric approach, and one that seeks a its object the inscriptions and material traces of digital memory, but it does so only at the cost of its own archivizaton—a digital le mal d’archive.

[1] Surprisingly, there is no clear translation of “forensic” in French. The term is usually coupled with a specific purpose, such as “médico-légal” for medical examiner.

The New Barbarians: The Postcolonial Hacker in the Age of Globalization (MLA 2015)

The following is a lightly edited version of the talk I gave at MLA 2015 in Vancouver, BC as part of the Postcolonial Digital Humanities: Praxis panel. A Storify of the full panel twitter stream (hashtag #mla15 #s14) can be found here.

The New Barbarians: The Postcolonial Hacker in the Age of Globalization

The new barbarians destroy with an affirmative violence and trace new paths of life through their own material existence.

–Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri

How do I relate myself — hypocrite lecterur! — mon semblable mon frère! — when I ambivalently occupy the place of ‘barbaric transmission’ which is also the negative space of civilization?

–Homi K. Bhabha

Whatever code we hack, be it programming language, poetic language, math or music, curves or colourings, we create the possibility of new things entering the world. Not always great things, or even good things, but new things. In art, in science, in philosophy and culture … there are hackers hacking the new out of the old.

— McKenzi Wark

Homi K. Bhabha opens his 2006 introduction to Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth with a question that any contemporary reader of Fanon must ask: “what might be saved from Fanon’s ethics and politics of decolonization to help us reflect on globalization in our sense of the term?” (xi). The answer, of course, is much, and Bhabha articulates those points of continued importance by emphasizing the way in which the cold war imposed a second Manichaean conflict for nations emerging from colonial rule. The political tug-of-war between the United States and Soviet Russia made the realization of a Third World a “project of futurity conditional upon being freed from the ‘univocal choice’ presented by the cold war” (xvii). As such, Bhabha argues that “Fanon’s work provides a genealogy for globalization that reaches back to the complex problems of decolonization” (xv). Continue reading

MLA 2015 Panel–Postcolonial Digitial Humanities: Praxis

I am pleased to be presenting at this year’s MLA conference in Vancouver. I will be giving a paper on hacktivism as a theoretical and practical inheritor of the anti-colonial movements of the early and mid-twentieth century (details). More importantly, however, I look forward to hearing from the diverse array of academics, librarians and activists who will also be participating in the roundtable. Please join us!

Time: Thursday, 8 January, 12:00 noon–1:15 p.m.

Location: West 111, VCC West

Hashtags: #mla15 #s14

Description

This roundtable explores the role of praxis in the academy by bringing together two fields that developed in seemingly unrelated trajectories within the humanities in the 1980s: postcolonial studies and the digital humanities. Postcolonial studies draws on continental theory and philosophy to probe the power dynamics that shape the relationship of colonized people to history and culture while the digital humanities integrates the study of the humanities with digitization and programming. Yet, over the past thirty years, the fields have intersected in surprising ways. Postcolonial scholars such as Deepika Bahri and George Landow used web technologies of the 1990s to advance the field, through early sites like Postcolonial Studies at Emory and the Postcolonial Literature and Culture Web as a form of academic praxis.

On Events in Ferguson, MO and the Limits of Empathy

I can’t understand what’s going on in Ferguson. Oh, I understand that the black citizens of the town are viscerally upset at the unjustified shooting and killing of an unarmed young man. But however much I may read about the events, the hurt, the feelings of betrayal, I can’t understand it.

You see, I’ve never felt targeted by the police. Despite the odd speeding ticket, I’ve always pretty much known that the police where there for law enforcement, which meant to protect me from those who break the law. I didn’t grow up in world where every interaction with the police included watching someone I care about being arrested or shot. Exerting all my powers of imagination and empathy, I can’t place myself in nearby Southeast DC and conceive of the police not as my protectors, but as my jailors. Placed in a threatening situation, my first impulse would be to call the police and ask for their protection. I would not assume that no matter what was happening outside my door, involving the police would only result in the loss (to jail or otherwise) of someone I care about.

I can know all the facts, all the names, see all the timelines of events and the eye-witness reports from Ferguson, but I can’t understand what’s going on there. Perhaps it’s because I will never, ever, be in danger of being shot in broad daylight by a police officer–no matter how disruptive I am being. I was born with the presumption of innocence, not guilt. Michael Brown was not.

Dear Supreme Court (who I can only assume read my blog)

I have been in a loving marriage for 15 great years. My wife, Diana, is a wonderful person and an amazing mother. Our two beautiful children are blessed by having two parents who love them, care for them, and worry about their well-being and happiness. Marrying Diana was the most important and best decision I have ever made–a decision that has produced tangible material, social, professional, and emotional benefits.

As you consider the arguments for and against same-sex marriage today, please know that my “traditional” marriage is not diminished or threatened by extending the benefits I describe above to those in a committed same-sex relationship that may wish to marry. Quite the opposite is true. We only strengthen the institution of marriage by making available the legal and social benefits it confers to any couple (gay or straight) who wish to commit their lives to each other.

When it comes to marriage there is no such thing as separate-but-equal. Civil unions are not marriage. They do not carry the full social and professional benefits of marriage, and since it is the state (not an ecclesiastical body) that confers marital status, we cannot deny same-sex couples the right to marry and still adhere to our highest ideals of justice for all. By making marriage just, we reaffirm it as an institution that merits its centrality in our social order.

So as you begin your deliberations, please keep in mind that to truly defend marriage is not to make it less accessible or less relevant, but to make it open and available to all couples, gay or straight, who wish to take on the responsibilities and benefits inherent in the institution.

Best regards, yours, etc., etc.

Porter

TL;DR